Academic RivalriesWhen Scientific Genius and Human Ego Meet

When Scientific Genius and Human Ego Meet

“If I have seen further, it is by standing on the shoulders of Giants.”

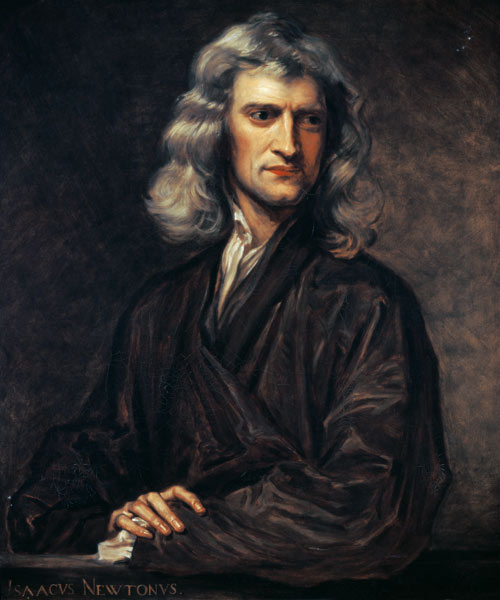

Isaac Newton wrote this in his letter to a fellow scientist, Robert Hooke. To most, it highlights Newton’s magnanimity, his selflessness, and devotion to the pure pursuit of truth. Surely, it is not a snide remark sarcastically denigrating someone’s stature—

But that is exactly what it is. A (slightly) mature middle-school feud.

|

| The pure pursuit of science一 except that it just isn't. Human beings are flawed. Credit: Symmetry Magazine |

We all fall prey to envisioning scientists as flawless, unique snowflakes who “boldly go where no one has gone before.” Why, scientists live and breathe discovery and truth. Unfortunately, as much as scientists love frequenting places like “The Unknown” and carry tools like “Math, Physics, and the will to explore,” they are also known to visit the more shadowy corners of the human experience—places like “Jealousy, Envy, and Hatred,” and bludgeon fellow comrades on the expedition to truth with the unsavoury methods of “corruption, power, and money.”

So, let’s dive in—not into the sweet sublimities of science, but rather the bitter rivalries, the cold exchanges, and the decades-long feuds between some of the brightest, most gifted minds humanity has ever known. Here we present, “The Great Academic Wars.”

Spoiler

Alert: It’s a lot like a cold war, but with no threat of nuclear annihilation.

Plenty of ego annihilation, however. Fair warning.

Newton Pulling Hooke Down—Or Was It Gravity?

|

| A portrait of Sir Isaac Newton painted by Godfrey Kneller Credit: Art Prints on Demand |

The feud between Sir Isaac Newton of apple fame and sinophile, polymath, philosopher, and Calculus co-inventor extraordinaire Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz is all too well known. Two incredibly intelligent men scrambling to gain credit for the science of limits and areas under curves—only that some guy, Archimedes, might have beaten them to the punch some 2000 years earlier by coming up with the foundations of calculus. But we aren’t going to talk about that, are we?

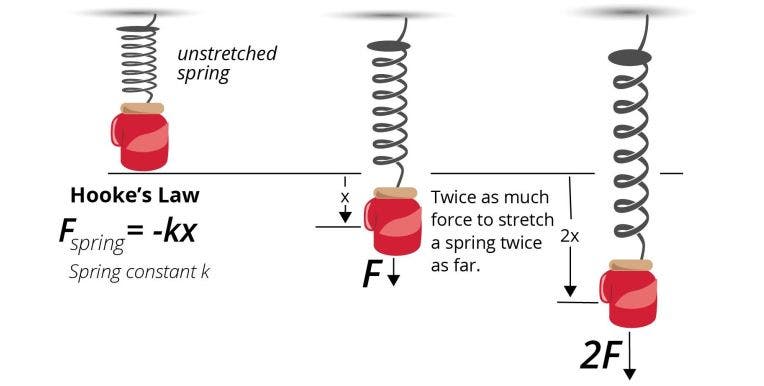

Robert Hooke

is a name that is familiar to all the groaning students in high school. Both

the Biology and Physics NCERT textbooks have mentioned him. Biology MCQs

worship him.

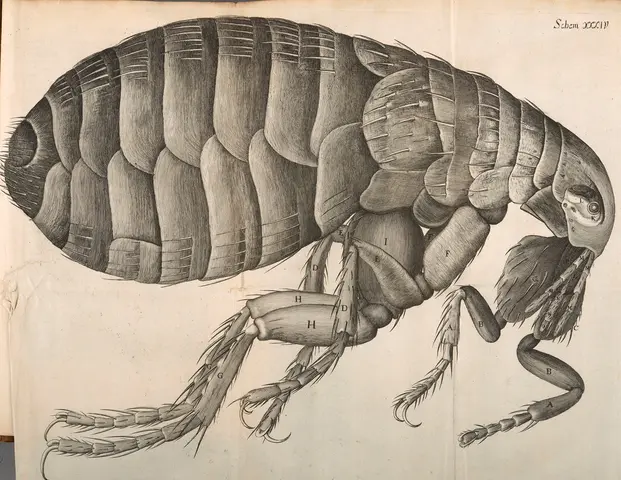

Indeed,

Robert Hooke was a man of many talents—an extraordinary physicist

("natural philosopher"), astronomer, geologist, meteorologist, and

architect. He was one of the first scientists to peer into the world of the

tiny creatures that inhabit our world. When he wasn’t busy sketching lice,

fleas, and cork, though, he was thinking deeply about springs and “their

springiness,” and about something else too—gravity.

|

| Hooke's Law governing the behaviour of springs to excellent approximation for small linear displacements Credit: Westlab Canada |

|

| Robert Hooke's incredibly detailed sketch of a flea as he observed it through his microscope Credit: Huntington Library |

|

| A page from Robert Hooke's "Micrographia" showing his sketch of cork Credit: Circulating Now, National Library of Medicine |

In the 17th century, many scientists, including Isaac Newton, believed in the aether as a medium for gravitational forces, while Robert Hooke proposed an alternative theory of gravitation in "Micrographia" (1665). Hooke argued that celestial bodies attract each other, and that this attraction increases as they get closer, though he did not yet define the exact mathematical relationship. In 1674, Hooke elaborated on this idea, asserting that gravitation applies to all celestial bodies, but he did not specify an inverse square law.

In 1679,

Hooke corresponded with Newton, discussing various scientific topics, including

the nature of planetary motion. Hooke proposed that gravitational attraction

might follow a relationship inversely proportional to the square of the

distance between bodies, but he did not have evidence or mathematical proof.

Newton, in his response, expressed doubts and eventually published 'Principia' in 1686, where he developed a formal mathematical theory of gravity and

acknowledged Hooke’s contributions, although he disputed Hooke’s claim to

having discovered the inverse square law.

|

| The all-too well known not-universal, "Universal Law of Gravitation". This law is an inverse square law. Credit: ResearchGate |

While Newton credited Hooke and others for their early ideas on gravity, he downplayed Hooke’s role, stating that Hooke's insights were unproven, unlike his own mathematical framework. Later assessments, such as those by Alexis Clairaut and I. Bernard Cohen, suggested that Hooke’s contributions were significant in the development of gravitational theory, even though he did not fully develop his ideas.

Bernard Cohen said: "Hooke's claim to the inverse-square law has masked Newton's far more fundamental debt to him, the analysis of curvilinear orbital motion. In asking for too much credit, Hooke effectively denied himself the credit due him for a seminal idea." Sounds like a school project gone wrong, doesn’t it?

Later, when Newton became head of the Royal Society, all of Hooke’s portraits mysteriously disappeared. Very few of his personal writings exist. Did Newton have something to do with it? Probably not. The fact is, to this day we do not know what Robert Hooke really looked like. Descriptions of his personal appearance, including his short stature, survive.

Regardless of the true circumstances, all this leaves an image of sparring scientists that

is too unpleasant to ignore.

|

| Portrait of a Mathematician by Mary Beale一 but which one? This probably isn't Robert Hooke, and is conjectured to be Isaac Barrow instead. Credit: Mary Beale |

| Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz, painted by Christopher Bernhard Francke Credit: Herzog Anton Ulrich-Museum |

I have a

confession to make—when I said we wouldn’t talk about Newton and Leibniz, I

lied. The truth is the beef between these two is simply too delicious to

ignore. Buckle up!

Newton, like the mathematician Gauss, was something of a perfectionist. Having begun work on the “method of fluxions and fluents” in 1666, what did Newton do? He buried his work deep in his desk, and only decided to publish it as a brief annotation in the back of one of his publications several decades later.

| Newton's work on Calculus, Analysis per quantitatum series, fluxiones ac differentias Credit: University of Oregon |

Leibniz, on the other hand, published his first paper on calculus in 1684—before Newton. Newton’s supporters accused Leibniz of plagiarizing Newton’s work, even though his notation was more exhaustive and algebraic, and Newton’s was geometrical.

|

| A tiny section of Leibniz's handwritten notes from the time he was inventing (or discovering?) calculus Credit: Stephen Wolfram |

This scramble for credit became a bitter dispute—one through which Newton fared better, as public opinion was on his side.

Circumstances proved fortuitous for Newton—for when he became president of The Royal Society, he set up a committee to pronounce on the priority dispute, in response to a letter from Leibniz. Leibniz’s account was never considered (I wonder why!) and the report of the committee ruled in favor of Newton. Apparently, “conflict of interest” simply did not exist in Sir Isaac Newton’s dictionary.

Modern historians and mathematicians credit both Newton and Leibniz with the development of calculus—both men independently stumbled upon this beautiful and fascinating branch of math that underpins all of modern physics. Extra points for Leibniz for his forbearance, though, and points redacted from Newton for his cruelty to poor Leibniz.

Also, as a calculus student, I am partial to Leibniz: after all, it is his notation, (and not Newton's) that is used by students of Calculus all over the world.

The End

of a Star’s Life, and the Beginning of an Intense Rivalry

|

| Indian-American astrophysicist Subrahmanyam Chandrasekhar Credit: Sunny Labh- Medium |

|

| British astronomer Sir Arthur Eddington Credit: ESA |

This is the tale of a scientist hanging on to his theories and rejecting what didn’t conform to his views—something that is all too familiar to us in the world we live in.

The heart of this dispute was a difference in what each believed to be the “correct theoretical framework.” Chandrasekhar, in the 1930s, had come up with a model of stellar evolution and the mechanism for a star’s death, all on a boat trip from Madras to England. Building on the work of Ralph Fowler, Chandrasekhar developed a stellar model that tried to analyze the motion of electrons in the extreme cores of stars through the lens of special relativity. He discovered that a white dwarf could not exceed a certain mass, a fact today known as the Chandrasekhar Limit. For years, Eddington would criticize the so-called “Chandrasekhar Limit” and denounce its existence.

|

| The upper limit for the mass of a white dwarf turns out to be about 1.4 solar masses. Any higher than this, and "electron degeneracy pressure" will fail to hold up the white dwarf star against the onslaught of gravity. Credit: Galileo Unbound |

Eddington openly demolished Chandrasekhar’s conclusions, an occurrence that deeply hurt and affected Chandrasekhar. A fledgling new scientist, this criticism from an established and vocal authority was a heavy blow to bear.

Jayant Narlikar, Indian physicist extraordinaire, writes on his blog,

“[Eddington] forcefully argued that the hypothesis as well as the conclusions of Chandrasekhar were physically meaningless. When an established scientist in the field passes such a strong judgment on his work, surely a young scientist must feel very crestfallen and dejected.

"Eddington went on to say that the conclusions drawn by combining quantum theory and relativity were wrong because such a combination is untenable. Moreover, he argued that, if the limit on the mass of white dwarfs were correct, what about the stars more massive than the limit? These stars would keep on contracting and, in the end, their force of gravitation would grow so strong that it would stop even the light rays! “I think there should be a law of nature to prevent the star from behaving in this absurd way,” he said.”

Ironically, it would be exactly this bizarre conclusion that would manifest in physical reality. You know them and love them—black holes.

|

| Movie rendition of a black hole一 Interstellar appreciation post Credit: Bohring- Substack |

While prominent physicists like Dirac, Rosenfeld, and Bohr supported Chandrasekhar’s line of reasoning, they did not openly criticize Eddington.

In spite of it all, Chandrasekhar would have the last laugh. 48 years later, in 1983, Chandrasekhar received the Nobel Prize in Physics, alongside William Alfred Fowler, for their "theoretical studies of the physical processes of importance to the structure and evolution of stars.” While Eddington never retracted his statements against Chandrasekhar and his work, Chandrasekhar nonetheless continued to consider Eddington a friend and even considered him one of the greatest astronomers of all time, alongside Karl Schwarzschild.

If it was a

rivalry, it certainly wasn’t from Chandrasekhar’s side! Moving on…

The Accelerating Expansion of Spacetime and Enmity

|

| French astronomer Gerard de Vaucouleurs Credit: Emilio Segrè Visual Archives |

| American astronomer Allan Sandage Credit: Calisphere |

The value of the Hubble constant is a bit of a contentious issue at present—but certainly not as contentious an issue to cosmologists today as it was to French astronomer Gérard de Vaucouleurs and American astronomer Allan Sandage, who bitterly fought over the ‘correct’ expansion rate of the universe.

Vaucouleurs and Sandage certainly were the best of friends—for when Sandage and his collleague Gustav Andreas Tammann acknowledged the error they had committed in understating the systematic error of their model in 1975, Vaucouleurs responded "It is unfortunate that this sober warning was so soon forgotten and ignored by most astronomers and textbook writers". Ouch.

The War

of the Currents (And no, that is what it is actually called—scientists are not

THAT bad at naming things)

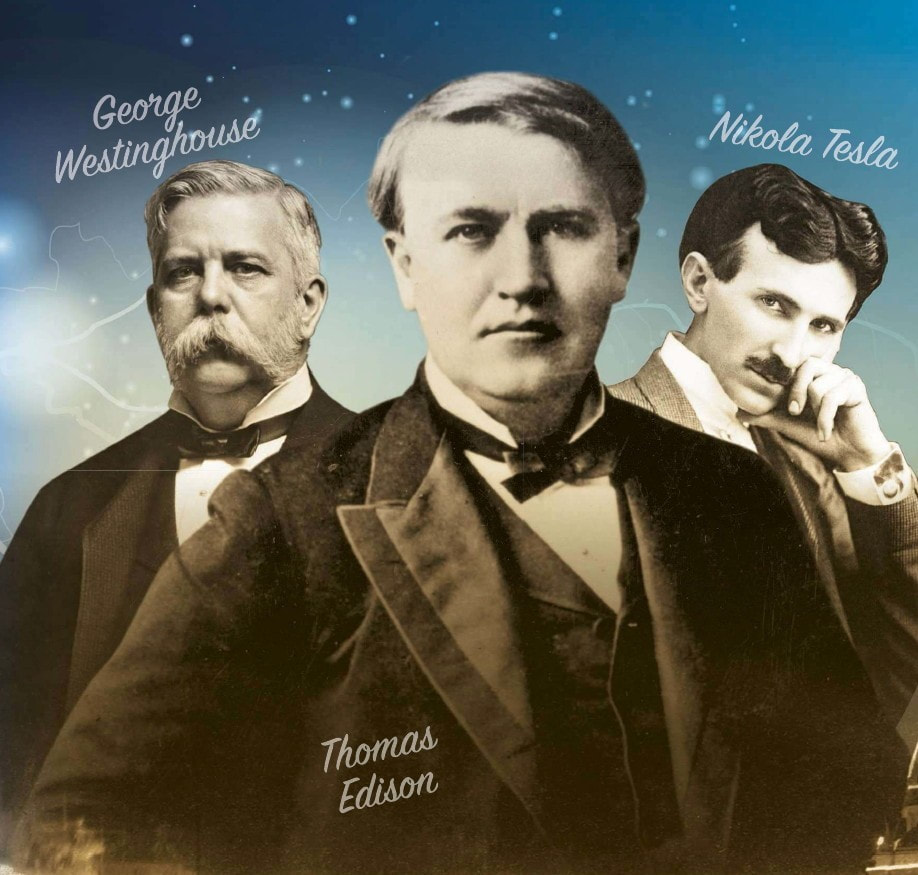

|

| The three main players in the 'War of the Currents'一 Westinghouse, Edison and Tesla Credit: Take a Walk New York newsletter |

The great

personal feud between Thomas Edison and the sensitive, tortured genius with a

growing fanbase, Nikola Tesla, has captured the public imagination. It’s got

all the elements of a great movie plot—the (somewhat) romantic setting of a

world caught in the second wave of the industrial revolution, a face-off

between a savvy entrepreneur and a sensitive mind, and ambition flowing in

larger volumes than current through the extensive networks.

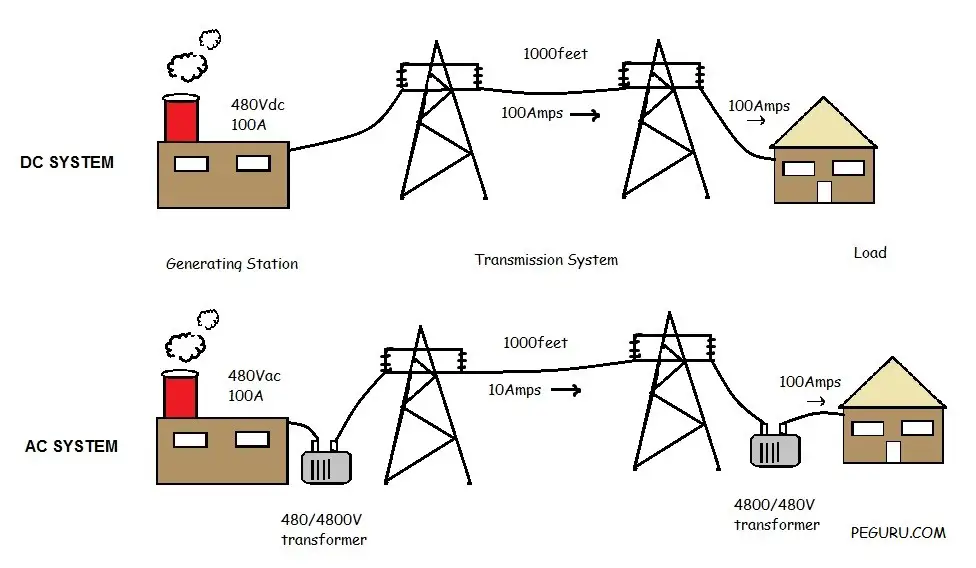

|

| The differences between AC and DC transmission systems. Notice the large amounts of current that must be transferred in the DC system, as well as the heavy losses. Credit: PEguru |

In the mid-1880s, Edison’s DC system was the dominant method for distributing electricity. However, Tesla, who had initially worked for Edison, developed AC technology and moved to Westinghouse’s company to help bring it to market. AC's key advantage was its ability to be transmitted over long distances by stepping up and down voltages with transformers, which made it more efficient and cost-effective for large-scale power generation.

The

Bernoulli Brothers…or the Bernoulli Rivals?

So far,

we’ve seen two individuals face off against each other. What happens when we

throw an entire family into the mix?

|

| The (infamous?) Bernoulli brothers Credit: Cantor's Paradise |

Enter the

Bernoulli family. This is as close as one can get to a science-themed soap

opera.

Read with a lot of interest. Couldn't help laughing at places and marvelling at others.

ReplyDeleteIt's a really good read. Language is lucid.

ReplyDeleteBrilliantly written! Informative, interesting and humorous all at the same time. Wish the young author all success👍🏼

ReplyDeleteVery well written article subtly explaining the ‘publish or perish' culture and the influence of funding agencies in scientific research. Pinch of humour added in the thought provoking article makes it a must read. All the best to the young publisher👏👏

ReplyDelete